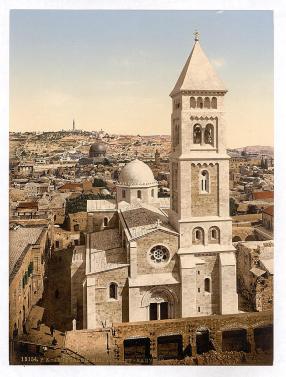

Redeemer Lutheran Church, viewed from the SE. The domes of the Holy Sepulchre appear in the background.

This post looks both back and forward: back to a visit I made to the site in August 2011 and forward to the anticipated opening to visitors of excavated areas under the church, plus a museum area, in the fall of 2012. If you didn’t know there were ancient remains under the church, don’t feel bad: For many, many years they have been viewable only by special request. At the same time, one might surmise that beneath any sizeable property within the Old City of Jerusalem might lie things of interest from antiquity, and the Redeemer Church is no exception.

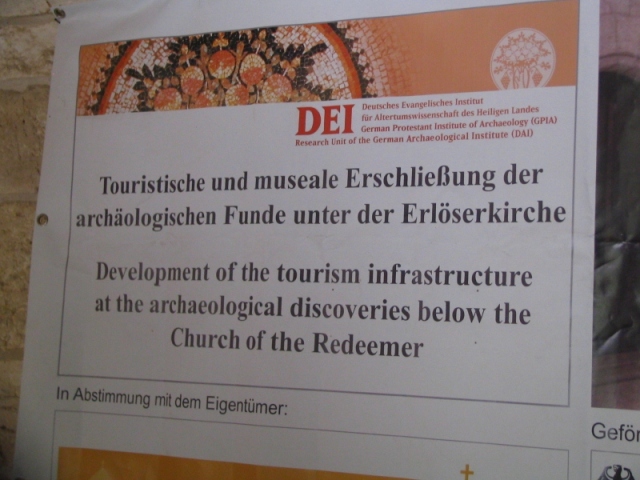

My recent visit to the place was a public tour offered in conjunction with an August 18-19, 2011 seminar sponsored by the German Protestant Institute of Archaeology in Jerusalem (GPIA) along with the Austrian Hospice. The occasion was a focus on the German theologian and orientalist Gustaf Dalman (1855-1941): the 70th anniversary of his death plus the launch of an international project “Gustaf Dalman’s Arbeit und Sitte in Palestina in Hebrew. A Commentary and translation”. (By the way, Todd Bolen of BiblePlaces.com likewise has a Dalman project in the works, a first-ever English translation of another of the scholar’s works.)

GUSTAF DALMAN: After the founding of the GPIA in 1900, Dalman – then Professor of Old Testament and Judaic Studies at the University of Leipzig – was appointed its first director in 1902 and served in that post until 1917 when, as a German national, his work in the Holy Land was cut short by the arrival of the British; back in Germany, he became once again a professor of Old Testament, until his death at age 85. Besides developing the program of the Jerusalem Institute, Dalman’s years of personal fieldwork in Palestine had actually focused on everyday peasant life, which was even then fast disappearing. Thus, one of his greatest contributions was the production of wonderfully detailed ethnographic studies, not only as pure documentation but, as he intended them, a window into life in the biblical world.

Since 1982 the GPIA in Jerusalem has been housed on the Auguste-Victoria compound on the Mount of Olives; from 1967 there has been a GPIA institute in Amman as well. Our tour beneath the Redeemer Church was conducted by the current director of the GPIA, Dr. Dieter Vieweger.

Lutheran Church of the Redeemer, ca. 1900 (photochrom print). Note that the Muristan area (bottom) is still being cleared for rebuilding as today’s Greek market. The only possible viewpoint for this unusual photo is the minaret of the Mosque of Omar near the Holy Sepulchre.

A bit of background: The Lutheran Redeemer Church lies in the heart of the Old City’s Christian Quarter, a ‘stone’s throw’ (to the southeast) from the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. It is a reflection, in part, of the intense interest that European nations began taking in the Holy Land in the 19th century — the waning days of the Ottoman Empire, and their desire to ‘stake their claim’ as it were through the building of churches, schools, hospitals and other such institutions. The property, the entire eastern half of the Muristan quarter, was obtained by the Prussian royal family in 1869. A church was then planned and designed, but not realized for several years. It was 1898 when the Redeemer Church, still under construction at the time, was officially dedicated by Kaiser Wilhelm II during his famous state visit and pilgrimage. The church and the adjoining historic structures underwent a complete renovation in the 1970s.

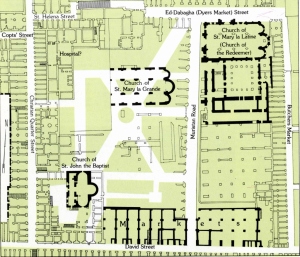

Map of the Crusader Muristan quarter. (Source: “Historical Atlas of Jerusalem” by Dan Bahat) – CLICK FOR LARGER IMAGE

The Muristan quarter — the name is from the Persian word for “hospital” — was for many centuries a center for the care of Christian pilgrims, perhaps as early as the time of Charlemagne. By the 11th and 12th centuries, first under the administration of the merchants of Amalfi in Italy assisted by Benedictine monks, and later that of the Crusader Knights of St. John — the Hospitallers, the Muristan had become a bustling place with at least three churches and related hospice and hospital facilities, some quite large.

The northeast corner of the Muristan was anchored by a large church known as St. Mary of the Latins. First built ca. 1070 and then rebuilt by the Crusaders about 1150, it became the monastic church of the Hospitallers. The rest of the order’s compound — cloister, dormitories and refectory — stretched to the south of the church, together constituting the Hospitaller’s headquarters in the Holy Land until the loss of Jerusalem in 1187.

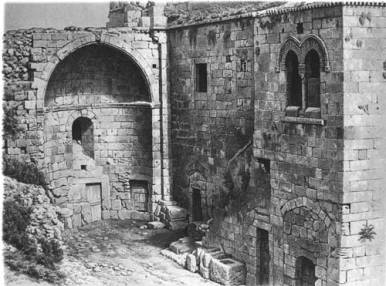

Ruins of St. Mary of the Latins (E. Pierotti, 1865). View of southern lateral apse and south wall, looking SE. The stairway (right) originally connected with the adjacent Hospitaller monastery. In the 1890s, the elegant double-arched window (upper right) was preserved and re-installed elsewhere in the Redeemer Church compound.

In the post-Crusader period the church slowly fell into ruin, but an 1865 photograph shows some of its walls and apses still standing to a considerable height. It was this church, the medieval St. Mary of the Latins, that the Prussians (later Germans) sought to recreate with the building of the Redeemer Church. The latter was indeed built on exactly the same spot, but with new foundations going down to bedrock (11 meters beneath the Crusader church) and its floor level standing 2 meters higher than the medieval floor. Almost none of the medieval church was preserved in the new construction, except that the deep northern portal, with numerous decorative carvings gracing its facade, was restored and incorporated into the new structure.

In preparing the site for the Redeemer Church in the 1890s, the workers discovered an ancient wall running on an east-west line, now known to be 1.6 meters thick and surviving to a height of 2 to 3 meters. This, indeed, is one of the highlights of the excavated area now being prepared for visitor access. At the time, the German explorer and architect Conrad Schick, among others, took this to be a section of the so-called Second Wall of Josephus (for a discussion of Josephus’ three walls, see my article on the Holy Sepulchre, pp. 3-5). The importance of this, if it were true, lay in providing additional evidence for the accuracy of the nearby Church of the Holy Sepulchre as the true place of Golgotha and the tomb of the resurrection, since John 19 specifies that Jesus was crucified “near [i.e., outside] the city”. In any event, the Second Wall identification — which seemed to find support in a presumed gate structure found in the nearby Russian excavations — was firmly embraced, and the ancient masonry came to be viewed as a sort of relic pointing to the Lord’s Passion. Thus it is not surprising that when the new church’s foundation stone was installed in 1893, it was placed directly atop this wall.

After the building of the Redeemer Church, new excavations were not undertaken until Ute Wagner-Lux and Karel Vriezen conducted a project from 1970 to 1974. Without disturbing the present floor, they removed all the modern fill beneath it, as well as the remaining medieval floor, in order to further explore what was below. Among other things, a deep sounding was made along the southern face of the ancient wall, going all the way down to bedrock. As a result of this work, the wall was reinterpreted: Due to the nature of its construction, it could not be a city wall. It was judged to belong to the Late Roman period (2nd to 4th centuries), a retaining wall for terracing, or perhaps the foundations of a small building, belonging to the upper forum of Aelia Capitolina. At the bottom of the sounding were the distinctive traces of the Iron Age quarry that is known to underlie much of the Muristan and practically all of the Holy Sepulchre church. (The quarry itself actually provides evidence in support of the Holy Sepulchre site, since the Second Wall is presumed to have skirted the quarry on the east, leaving the quarry as a sort of defensive moat — outside the city wall.) Anyway, on with the tour…

Atop the wall sits the “Foundation Stone”, a sort of time capsule installed during the church’s construction.

The Foundation Stone of the modern church, put in place in 1893, was opened for the first time this past summer (2011), by Dr. Vieweger. For more on this unusual event — including an intriguing mystery, presumably still unsolved — see HERE: https://www.church-of-the-redeemer-jerusalem.info/excavation/foundation#top.

The following four images form a sequence, giving a sense of the levels uncovered here, from top to bottom. It shows that the wall was founded on a bed of smaller stones laid directly on a thick fill of soft earth. Thus the wall, despite its size, was incapable of supporting any great weight. The thick fill layer probably represents the Roman leveling of the old quarry for the construction of Hadrian’s forum. The latter pictures are looking down into the deep rectangular sounding from the 1970s, right down to bedrock.

Dr. Vieweger points to the large ashlar-built wall. A later arch spans the wall cross-wise. (And, yes, that’s the ubiquitous Dr. Gabi Barkay at lower right)

The excavated area, looking west. Many of the remains here Vieweger relates to the Constantinian Holy Sepulchre complex.

Again, the opening of these spaces to the public is slated for the fall of 2012.

UPDATE 2020

For much more background on the excavation areas, and the now fully developed exhibition spaces off the cloister (both open to the public for the past few years), see the church’s upgraded website HERE: https://www.church-of-the-redeemer-jerusalem.info/excavation/index#top

Reblogged this on Project Peace and commented:

We shall visit this church on this delegation to Palestine, May 6-